What is Digital Public Infrastructure?

David Eaves and Jordan Sandman

At Co-Develop, we understand digital public infrastructure (DPI) to be society-wide, digital capabilities that are essential to participation in society and markets as a citizen, entrepreneur, and consumer in a digital era. Because it is essential, DPI should be guaranteed by public institutions to be 1) inclusive, 2) foundational, 3) interoperable, and 4) publicly accountable, as it is deployed in countries around the world.

If you'd like to learn more about why we wrote a definition, please see our framework explainer.

Co-Develop’s mission is to catalyze the global adoption of safe, inclusive, and equitable digital public infrastructure (DPI). Given increased interest in DPI, this post seeks to contribute to an ongoing debate by laying out a framework for how to understand, design, and deploy it.

Public infrastructure is critical to our lives

Transportation networks, electrical grids, and telecommunications systems are all examples of infrastructure that have catalyzed enormous economic, social, and political progress by supporting the creation and delivery of innumerable private and public goods. Despite, or maybe because of, its ubiquity and critical importance, infrastructure remains difficult to define. At its core, we share Brett Frischmann’s view of infrastructure as “shared means to many ends.” For example, roads (the shared means) are a common way to transport individuals or goods for a range of purposes – to get to hospitals, schools, or grocery stores, or anywhere else for any other reason (the many ends).

Some forms of infrastructure are so critical to the functioning of societies that inequitable access – for whatever reason – can lead to significant social and/or economic harm. These harms may be as a result of poor management that leads to inconsistent provision, specific design choices that lead to exclusion, or because the infrastructure becomes a natural monopoly that creates cost barriers. Under these conditions, governments intervene into markets by taking on regulatory or financial roles as a guarantor of those capabilities in service of the public interest.

Infrastructure guaranteed by governments is known as “public infrastructure.” Public infrastructure is so critical that innumerable specialized institutions from local governments to the World Bank are chartered to support its funding, development, maintenance, and oversight.

What qualifies as public infrastructure in the digital age is evolving

Deciding which capabilities are public infrastructure is fundamentally a political choice. During the 1990s and 2000s, most countries came to view telecommunications – and in particular cellular and broadband data – as a new form of essential infrastructure and stepped in as regulators to ensure broad access. Now, as everything from government services, access to capital, and participation in markets is mediated by digital systems, countries are asking similar questions about some key online capabilities – and arriving at the conclusion that yes, there is a new “digital public infrastructure” (DPI) that needs to be defined and supported.

The definition of this new form of infrastructure is still emergent with a number of organizations including GovStack, the World Bank, the Centre for Digital Public Infrastructure, and EkStep Foundation contributing to the conversation.

At Co-Develop, we understand digital public infrastructure (DPI) to be society-wide, digital capabilities that are essential to participation in society and markets as a citizen, entrepreneur, and consumer in a digital era. [1]

The Components of Digital Public Infrastructure

The set of capabilities that enable participation in society is constantly evolving, but over the past two decades, several countries have converged on three capabilities that they manage as digital public infrastructure, specifically the ability to:

1. Digitally verify identities

2. Securely send or receive money

3. Safely exchange personal information

While these capabilities are privately provisioned in many places, a growing number of governments have used a combination of public and private ownership, regulation, and provision to govern them as public infrastructure. Deploying digital identity, payments, and data exchange as public infrastructure allows societies to prioritize access, local sovereignty, interoperability, and safeguards for systems that might otherwise optimize for specific populations or profits.

So what makes these three particular capabilities so critical that they have become public infrastructure in the 21st century?

Identity

Digital identity allows individuals and organizations to establish who people are, what they own, and what they have access to – capabilities that form the foundation of any society in the 21st century. People who are excluded from legal identity, including 850 million individuals worldwide, struggle to access bank accounts, demonstrate ownership of property and other valuable goods, assert their eligibility to access public benefits, and establish credit. Digital identity can streamline and increase access across entire populations, especially among marginalized groups. Aadhaar, India’s digital identity that reaches over 1.3 billion people, is a good example of an identity system deployed at population scale.

Payments

Digital payments infrastructure provides a common network that allows private organizations, public agencies, and individuals to instantly send and receive money. This means transactions are not siloed by sector or subject to rent or data extraction by a dominant payments provider. Instead, payments infrastructure is inclusive, facilitating competitive markets for users and last-mile providers. Paired with digital identity, digital payments infrastructure could be a way to include the 1.4 billion people who are unbanked and bring them into formal economic participation by offering a more secure, seamless way to transact. A good example is Pix, Brazil’s digital payments system that has reached 76% of the adult population in just two years after its launch.

Data Exchange

Data exchange capabilities allow public and private sector organizations to securely share information – with individuals’ consent – to facilitate the delivery of services. Public sector data sharing is often technically challenging, and even when possible relies on a patchwork of agreements that impede accountability and transparency. Standardizing how information is collected and shared by public institutions can make it easier for individuals to gain access to services. For example, individuals can use data exchange to share their health records with their doctor and pharmacist or their income level with social assistance and tax administrations. Businesses can share data about goods and services they administer to improve supply chains. X-Road, Estonia’s data exchange system, is a good example.

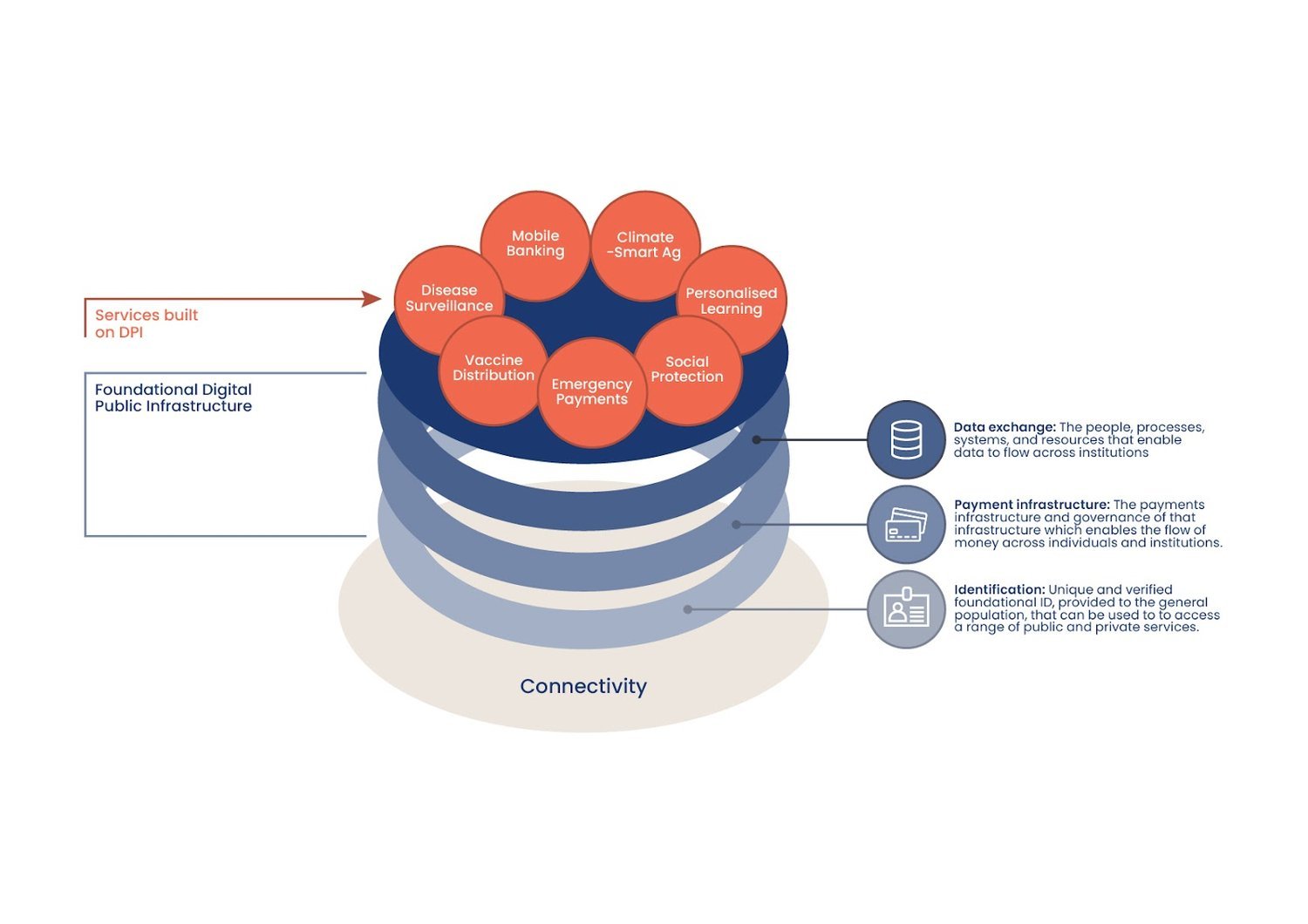

Together, these three areas represent public infrastructure that every country will need to build in the 21st century, enabling solutions to a broad number of societal problems to reach scale.

Image Credit: Digital Impact Alliance

It is worth noting that there are also sector-specific systems that function like digital public infrastructure within a specific domain. These might include digital public services, health care records, climate emissions monitoring, communications, and digital land mapping for agriculture. These are critical capabilities, and over time, they may become so important that they become considered as digital public infrastructure. Our goal here is to provide a baseline definition that focuses on the most common infrastructure cases that transcend domains.

Designing Digital Public Infrastructure

Building DPI is not just about digitizing sectors by mapping new technologies to analog solutions, in contrast to other digitization efforts. Public infrastructure thinking requires both a new mindset that specifically takes advantage of the scalability of technology systems and prioritizing public interests.

There are a few principles that are generally common to all forms of public infrastructure that should also guide the deployment of digital public infrastructure. Infrastructure should be:

1. Inclusive: public infrastructure should be nearly universal, and exclusion should be rare. For example, in the physical world, we believe everyone should have access to roads, water, and electricity should they choose it. In the digital world, citizens that cannot access a digitally enabled identity may not be able to access public benefits, vote, or establish a bank account.

2. Foundational: anyone should be able to use and build on top of public infrastructure. Electrical grids are not important because electricity is itself useful but because it makes possible services built atop of it, such as entertainment, appliances, and life saving equipment. With few exceptions, anyone can create and use products powered by electricity for any purpose without permission. Digital public infrastructure like payments and ID should be similarly extensible: organizations of any kind should be able to use these systems to accept and make payments or verify someone’s identity.

3. Interoperable: for public infrastructure to be inclusive and foundational, it must use interoperable, open standards. Standards are what makes possible the “shared means” that enable the “many ends” that infrastructure serves. For example, it is the standardization of voltage, amperage and plug sockets that enables a diverse range of appliances to use electricity. Digital infrastructure should be similarly interoperable: clear standards should enable a competitive ecosystem that can both supply the infrastructure’s underlying components and the “many ends” and services built on top of it.

4. Publicly accountable: Private infrastructure may be foundational, inclusive, or interoperable, but it might also not be. Market forces or other incentives might lead infrastructure to be exclusionary or siloed. What makes infrastructure “public” is a publicly accountable governance mechanism for enforcing these traits. This requirement for effective governance has two implications for DPI:

o First is that, when it comes to public oversight, government participation alone is insufficient. DPIs need governance models that include a diversity of stakeholders to ensure accountability to the public interest. Citizens of affected groups and civil society should be included in the process of designing infrastructure to avoid harm or exclusion.

o The second is that if DPI is to be held accountable to the public interest, then governments providing oversight need mechanisms – via ownership, regulation, policy, and/or law – to enforce that accountability.

We acknowledge that there will be variance in how countries deploy DPIs, such as how they are governed, financed, and maintained. For example, some envisage governments as the builders and maintainers. Others believe it will be more effectively provisioned by private sector firms with governments taking a passive role at best. Still others imagine versions that blend the two or adopt alternative models. What is essential to us is that DPI systems meet these five key characteristics – that it is inclusive, foundational, interoperable, publicly accountable, and local sovereign.

Building identity, payments, and data exchange as infrastructure to scale solutions in agriculture, health, poverty, climate, and other pressing challenges promises to be one of the most compelling public interventions of this decade. But the work, as with the definition of it, is still emergent. We look forward to hearing from you to learn more ways to think about these important issues.

—————

[1] Note that our definition excludes broadband connectivity, which we would consider to be increasingly defined as a form of physical infrastructure.